Research says that she was Circassian and that she was also a slave.

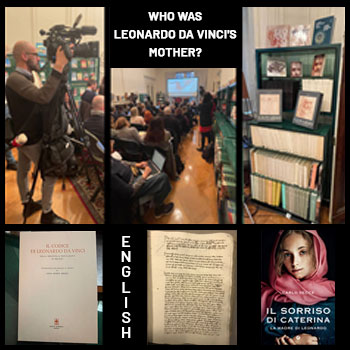

Florence, Italy, 14 March 2023 – Presentation of the book “Il sorriso di Caterina” (Catherine’s smile) by Carlo Vecce, at Villa La Loggia in Florence, Italy, in the prestigious headquarters of Giunti Editore

With Giunti Editore, Carlo Vecce publishes a fictionalized biography of Caterina, the mother of Leonardo da Vinci. A fascinating and engrossing story, inspired by the discovery of important, previously unknown documents. Texts that shed new light on and open a new chapter in our knowledge of Leonardo’s origins, in the context of a long-standing and complex debate.

A marsh at the mouth of the Don River, on the Sea of Azov. A July morning. A girl is torn from her native land, enslaved, sold over and over again by a network of human traffickers. When she reaches Italy, she occupies the lowest rung on the human and social ladder, she has no voice, no dignity. They have taken everything from her, her body, her dreams, her future, but she will show her strength. The strength to suffer, to struggle, to love, to give her life, to regain her freedom.

It could easily be a story of today, rather than from a distant, almost legendary past. And this was what stunned Carlo Vecce, a researcher and well-known and accomplished scholar of the life and work of Leonardo. One day, a new document forced him to pick up anew the trail of Caterina, Leonardo’s mother, and to look at things in a completely different way. Little by little, emerging from other documents and manuscripts were signs of forgotten existences, of lives that intertwined with one another, by the force of chance or destiny. Real people not imagined characters. Adventurers, prostitutes, pirates, slaves, knights, noblewomen, farmers, soldiers, notaries. Their stories unfold in reverse from Vinci to Florence, from Venice to Constantinople, from the Black Sea to the wild plateaus of the Caucasus.

Leonardo, as we know, was the illegitimate son of a young Florentine notary, Piero, and a woman named Caterina. Of her we knew almost nothing, except that she was married by an obscure farmer from Vinci, shortly after Leonardo’s birth. The only certainty was that in the shaping of her son’s extraordinary interior world, of his relentless pursuit of knowledge and freedom, the figure of his mother must have been decisive. She was the true mystery of his life.

Furthermore, in scholarly circles the hypothesis that Caterina was a slave had been circulating for several years: a hypothesis with scarce documentary support until now, though certainly not implausible. Early modern slavery, which made its way to the Americas, was born in the Mediterranean in the later Middle Ages. A story that’s little known, embarrassing, repressed, seeing as we Italians participated in it too. It was a lucrative business for the Venetian and Genoese merchants: female and male slaves, referred to as “heads” in the documents, were more profitable than spices and precious metals. In Florence the market demanded young women above all, destined for use as servants, caregivers, as well as concubines – sexual slaves who, if impregnated, continued to be useful even after giving birth, providing their milk to the master’s children.

The previously unknown document that Carlo Vecce found in the State Archives in Florence is the act of liberation of the slave Caterina by her mistress, Monna Ginevra, who two years earlier had rented her out as a wet-nurse to a Florentine knight. The document is written in the hand of notary Piero da Vinci: Leonardo’s father. We’re in an old Florentine home, behind the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, in early November 1452. Leonardo is just six months old, and he too is surely there, in his mother’s arms. Rarely, in the documents of this young but already scrupulous notary, do we find so many mistakes, so many oversights. That slave is “his” Caterina, the girl that gave him her love; that child is his son. Piero’s hand trembles, a strange emotion takes hold of him. He is so overwrought that he doesn’t even write the date correctly.

How did Caterina reach Florence? Thanks to Monna Ginevra’s husband: an old Florentine adventurer named Donato, previously emigrated to Venice, who owned slaves from the Near East, the Black Sea region and Tana. Before dying, in 1466, Donato left his money to the small convent of San Bartolomeo a Monte Oliveto, outside Porta San Frediano, for the construction of a family chapel and for his own burial. His trusted notary, yet again, is Ser Piero da Vinci. And Leonardo creates his first painting for that very church: the Annunciation. It’s no coincidence.

Piero da Vinci certifies that Caterina is the daughter of Jacob, and that she is Circassian. She comes from one of the world’s freest, proudest, most untamed peoples. She is Leonardo’s mother, she is the one who raised him until age ten, and the consequences of this discovery are staggering: Leonardo is half-Italian. As for his other half – perhaps his better half – he is the son of a slave, of a foreigner who didn’t know how to read or write, whose grasp of the Italian language was likely negligible. What lullaby might she have sung to help him fall asleep? What did she tell him of her own origins, of the amazing region where she was born, of the primordial sagas of her lost people? Of one thing we can be sure. She is the one who passed on to him a respect and veneration for life and nature, and an inexhaustible desire for freedom. She is the one who gave him her smile, tender and ineffable. A smile that Leonardo pursued his whole life, and that he thought he found in the face of a Florentine woman named Lisa.

Carlo Vecce eventually realized that he could no longer tell this story from without, from the point of view of the researcher or historian. He listened to the voices of the people he encountered on his journey: they will be the ones who tell us about Caterina. The story is entirely hers, hers and not others’ – not even Leonardo’s. The story of a woman, of a girl who crossed the sea, as so many other do today, all around us.

And the story continues even now, in the present day, beyond the pages of this book. In Milan, behind Sant’Ambrogio, amidst the construction of the Catholic University’s new campus, the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, which once housed Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks, is coming to light. Reappearing is the wall against which the altar stood, the floor that contained the crypt, the fragments of the starry sky painted on the ceiling by the Zavattaris. Then, an extraordinary discovery: in the crypt, mixed together, are human remains from centuries-old burials. Perhaps even those of Caterina, who in 1494 died in Milan in her son’s arms and was buried in this very place.

This book holds a wholly unique place in the catalogue of Giunti Editore, which has long been committed to promoting the figure and work of Leonardo da Vinci at all levels, from popularization to scholarly research. An old – and direct – bond that dates back to the very origins of the Giunti family in the Renaissance: the great printer Filippo di Giunta was an assiduous client of notary Ser Piero da Vinci, and his books were present in the library of one truly voracious reader: Leonardo.

Thanks to the commitment of Renato and Sergio Giunti, the Florentine publishing house, which in 2021 celebrated its 180th anniversary, has methodically created the monumental “National Edition” of all Leonardo’s manuscripts and drawings, with the collaboration of eminent scholars such as Carlo Pedretti, Augusto Marinoni, Anna Maria Brizio, Paolo Galluzzi, Martin Kemp, Pietro C. Marani and others. A cultural adventure that began in 1966 and that is further enriched today by another important contribution.

CARLO VECCE THE AUTHOR

CARLO VECCE, scholar of the civilization of the Renaissance, has dedicated himself primarily to the figure and oeuvre of Leonardo da Vinci. For Giunti he has published, with Carlo Pedretti, the Book of Painting (1995) and the Codex Arundel (1998), as well as numerous other works, including the recent The Library of Leonardo (2021). He has overseen cultural cooperation programs in India and China and has been seconded to the Accademia dei Lincei. He teaches at the University of Naples “L’Orientale”.

Book tour: dates and locations

Carlo Vecce’s book will be presented to the public for the first time on Wednesday 15th March 2023 in Florence, at the Galileo Museum (address: Piazza dei Giudici, 1) at 6:30 pm, with Paolo Galluzzi, member of the Accademia dei Lincei, and Helena Janeczek, writer and Premio Strega winner, in the presence of the author and the Museum’s Director, Roberto Ferrari (reservations required; for information: info@museogalileo.it, ph: +39 055/265311).

The other dates are: Thursday 23rd March in Rome – 6:30 pm – at libreria Ubik Spazio Sette (address: via dei Barbieri 6); on Thursday 30th March in Naples – 6 pm – at Palazzo Venezia (address: Via Benedeto Croce, 19); on Thursday 6th April in Paris (France) – 7:30 pm – at Librairie Tour de Babel (address: 10, rue de Sicile – 75004 Paris) and on Friday 7th April in Milan – 6 pm – at Libreria Rizzoli Galleria (address; Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, 11/12).

Contacts Giunti Editore

Jacopo Guerriero, Press Office Manager

Francesca Leo, Press Officer

Daniela Adorno, Press/Events Office

GIUNTI EDITORE: THE FACSIMILE EDITION OF LEONARDO’S MANUSCRIPTS

by Claudio Pescio – Director, Art Division, Giunti Editore

THE DA VINCI CODICES

The encounter between Giunti Editore and facsimile publishing did not stem from a general desire to reproduce marvellous pages from illuminated manuscripts, but from a more circumscribed passion for the life, work, and thought of Leonardo da Vinci.

For Giunti the publication of facsimiles represents a piece of the broader sector of art books, exhibition catalogues, guides, monographs, and the magazine Art e Dossier.

Facsimile publishing constitutes a crucial sector for the publishing house: it possesses an almost foundational importance, because for over fifty years the identification of Giunti Editore as the publisher of Leonardo has been one of the strongest components of its cultural image.

Over time, there has developed around the facsimile core a sort of separate section of bookshop products entirely dedicated to Leonardo (monographs, studies, the journal Achademia Leonardi Vinci, the “Letture Vinciane” series, even volumes of a more popular nature).

Facsimile publication also entails – and this is obviously true in Leonardo’s case as well – the creation of new, non-facsimile products, with original scholarly texts analysing the transcribed text of the codices. An operation that stimulates the field of studies, providing new academic texts to philologists, codicologists, historians and art historians.

Giunti’s experience in the facsimile field thus represents a unique case. It is essentially a cultural operation, but seeing as this is Leonardo, the codices’ facsimiles have inevitably ended up captivating the world in a unique manner, because they represent a gateway to the most intimate sphere of an utter genius. They are notebooks in which the artist and scientist took notes; pages on which he sketched his first visual ideas for an architectural or mechanical design, a distinctive anatomical trait, the possible position of one of the apostles in the Last Supper. It is clear, therefore, that the man-book encounter made possible by these facsimiles concerns not just scholars, but a potentially far broader public. Compared to his extraordinary but numerically limited pictorial production, the codices cover the entire trajectory of Leonardo’s adult life: from the mid-1470s to 1519, the year of his death. Not only do they reveal all of his many fields of interest, but his psychology, his opinions, his doubts, his difficulties, his spur-of-the-moment curiosities. The codices contain “all” of Leonardo. Then there is the history of the intrigues, the adventures, and the thefts of pages and entire notebooks that the codices have experienced over the centuries.

It all began with a lecture on Leonardo that Eugenio Garin gave in Florence back in 1961: “The Universality of Leonardo.” Among those present that day were publisher Renato Giunti and his son Sergio, the group’s current president. That was where this passion for Leonardo and his oeuvre was born, and the Leonardo Project as well – an unprecedented publishing enterprise that officially commenced in 1964. In that year, indeed – after careful evaluations by the academic world – the editing and reproduction in facsimile form of all the codices and drawings of Leonardo da Vinci was entrusted to the publishing house of Giunti in Florence, with a decree from the President of the Italian Republic and under the support of the Da Vinci Commission. Thus took form the monumental collection known as the “National Edition of the Manuscripts and Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci”. A project characterised by the highest editorial quality and accompanied by transcriptions and commentary conducted with the most rigorous philological criteria, with the collaboration of the finest Leonardo scholars such as Anna Maria Brizio, Ladislao Reti, Augusto Marinoni, Nando De Toni, Carlo Pedretti, André Chastel, Ludwig Heydenreich, and Mario Salmi.

For the first time the owners of all of Leonardo’s codices, conserved in various locations around the world (Milan, Turin, Rome, London, Windsor, Madrid, Los Angeles, Venice, Paris), provided direct access to the originals for their official reproduction.

The National Edition’s first volume came out in 1971.

998 facsimile reproductions are made of each codex, hand-numbered from 1/998 to 998/998. The volumes are accompanied by a handwritten notarial certification.

Today the enterprise – including codices and collections of loose pages – has nearly come to an end: only a couple of collections remain.

AUDIENCE

Facsimile publishing means publishing of the highest quality, with elevated prices. It goes against the grain of a more general conjuncture in which publishers are focusing their efforts on low and medium price ranges. Yet this is an approach that is absolutely in line with the popularizing vocation that characterised Bemporad, Martello, Marzocco and all the trademarks that have become a part of the Giunti group: even a facsimile may be understood as a work of popularization, in the sense that it transforms something from inaccessible to relatively accessible. Often, indeed, such texts are not even accessible to scholars who are specializing in the subject. We should not forget that Leonardo has a calligraphy that is only legible to a few specialists in the world, and that his world of cultural references is only familiar to a restricted group of scholars. Accompanying the facsimiles with transcriptions in a comprehensible language (as well as a diplomatic edition) has made a substantial contribution to universalising Leonardo’s thought and work.

This operation, then, has from its conception been directed through three channels and at three target audiences simultaneously: the world of culture, of philologists, of art historians; the world of collectors and bibliophiles more generally (those who typically purchase so-called “great works”, encyclopaedias, or beaux livres); and institutions, such as universities, museums and libraries.

Some buyers of the facsimiles consider their purchase to be a status symbol or investment. Scholars often turn to libraries to consult the codices, even if few public institutions are now able to make purchases of this sort; purchases by libraries represent roughly 5% of sales. The facsimiles of Leonardo’s Codices are now sold 60-70% of the time abroad, particularly to buyers in Spain, South America, and now even in China. We should not forget that the object of attention, in this case, is less the facsimile than the figure of Leonardo da Vinci himself, who in China, for example, enjoys great renown.

In the very near future, on the other hand, the world of culture will increasingly look to digital products, consultable without leaving one’s desk. It is an inevitable path, in this as in many other sectors, and I believe it is a correct and profitable one. Virtual consultation allows for a first approach to the work, even if it will never be able to replace the direct or semi-direct experience that a facsimile permits. It creates an intermediate step, broadening the potential audience and the number of specialist interlocutors, a condition that can foster the formation of a new audience; a conscious audience that is interested in the true contents of the “Da Vinci Codices”, which truly are rich in mysteries waiting to be unveiled, though perhaps more in the realms of the human sciences, hydraulic technologies, anatomy and botany than in the mysterious conspiracies of occult sects.

In any case, interest in a facsimile is clearly fuelled by a wholly different type of passion – one for which a virtual experience is no substitute.

ORGANIZATION OF THE EDITORIAL WORK

Unlike with publishers for whom facsimiles are their core business, Giunti’s structure is devoted prevalently to traditional book publishing, such that the facsimiles’ productive organization does not inhabit a world of its own but is rather intermixed with the rest of the publisher’s production.

Each volume has a curator (sometimes more than one), always a Leonardo specialist. The editor interfaces with the curator and oversees all the project’s various phases, assisted by a graphic designer and a technician for printing and colour.

The editor and curator identify the title to publish, in accord with the Da Vinci Commission. However, in the case of a publisher that has chosen to publish Leonardo’s works on paper, the publication plan is simply the one dictated by Leonardo himself: everything that presently exists, in the hopes of new discoveries. It is a matter of organizing the publications according to a scholarly and marketing logic. The publisher subsequently contacts the institution that possesses the original and the two parties negotiate compensation for the reproduction rights.

Next comes the photographic reproduction of the original – now entirely digital – under the control of the owner institution (unless the institution itself is able to provide high-quality images). Photography and sales are the only stages not carried out by the publisher; everything else occurs in-house.

Once the texts and photographs are ready the editing work begins.

At the same time, the specialized printing facility acquires the materials for printing and binding. The paper is special and chosen on a case-by-case basis in collaboration with the libraries and curators. For a printed result that is absolutely faithful to the original codices – such as the characteristic shades of Leonardo’s inks and the paper colour that the master used – a special print colour chart has been developed.

The technician works on the images with the supervision of the curator and the heads of the institution that owns the original, through a direct comparison with the original itself, creating colour proofs which are then subsequently finalised. It should not be forgotten that Leonardo’s codices are not illuminated manuscripts, books of hours, or missals with brightly coloured illustrations, gilding, or precious decorations; they are a vast collection of notes and drawings, normally in a single colour: the sanguine ink (diluted ferrous oxide) that Leonardo habitually used.

As previously mentioned, each edition of Leonardo’s codices is accompanied by a volume of transcriptions and commentary that facilitates a correct and thorough comprehension of the texts. For the diplomatic transcriptions of the Codex Atlanticus in the 1960s, London’s Monotype developed roughly two hundred and fifty special print characters to reproduce certain graphic symbols that Leonardo used in his notes and which otherwise would have been impossible to reproduce.

The specific artisanal binding workshop created at the printing facility acquires the materials for binding and sees to the production of the external case, entirely handmade. The materials used are calfskin leather, silk, wood or pure gold for the impressions; the punches are in brass, for maximum precision, and are impressed with a manual balance wheel. The binding is also handmade, with perforations that reproduce even the smallest imperfections of the original. Leonardo bound his notebooks by hand as well; he always worked with folio pages of the same size (circa 60 x 100 cm) and changed only the number of folds; when he acquired the pages they were unfolded, or at most fold in four. They generally came from factories in Fabriano, Pescia and Lucca. What’s interesting is that Leonardo sometimes left the original page unfolded and wrote on it, organizing the small pages based on the fold that he would later make. The leather and paper bindings were all made after his death.

National Edition of the Manuscripts and Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci:

Codex Atlanticus, 1971-1980, 12 volumes of plates + 13 volumes of transcriptions and commentary Madrid Codices, 1974, 5 volumes of plates + a volume of transcripts and commentary

Codex on the Flight of Birds, 1976, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Codex Trivulzianus, 1980, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary Manuscripts of the Institut de France, 1982, 12 volumes of plates + 12 volumes of transcriptions and commentary

Corpus of Anatomical Studies, 1983, 3 volumes of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and His Circle at the Uffizi, Florence, 1985, 1 volume

Codex Hammer, 1987, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and His Circle at the Royal Library in Turin, 1990, 1 volume

Forster Codices, 1992, 3 volumes of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and His Circle in American Collections, 1993, 1 volume

Book of Painting, 1995, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Codex Arundel, 1998, 2 volumes of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and His Circle at the Accademia in Venice, 2003, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and His Circle in France, 2008, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and His Circle in Great Britain, 2010, 1 volume of plates + a volume of transcriptions and commentary

Special Edition for the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Leonardo Project:

I – The Hundred Most Beautiful Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. The Artistic Realm

II – The Hundred Most Beautiful Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. Machines and Scientific Instruments

III – The Hundred Most Beautiful Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. Anatomy and Studies of Nature IV – The Hundred Most Beautiful Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. The Four Natural Elements: Land, Air, Fire and Water

V – The Hundred Most Beautiful Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. Codex Trivulzianus and the Codex on the Flight of Birds